A tiny Chinese porcelain teapot made during the Kangxi period (1662-1722) combining three of my favorite things: inventive repair, miniatures and clobbering. It’s hard to tell what the original 1700’s underglaze decoration was, as the multi color & gilt overglaze decoration of dragons & flowers extends over the entire surface.

Clobbered in the early 1800s to satisfy the demand for more colorful pottery of the times, this small teapot stands 4-3/4″ tall.

There is a hole connecting the spout to the body, as well as a tiny hole in the lid for steam to escape, confirming this to be a functioning miniature.

This piece has travelled much over the past 220 years, as it was originally made in China, exported to Europe, clobbered most likely in Holland, landed in Scotland with a collector and ended up with me in America!

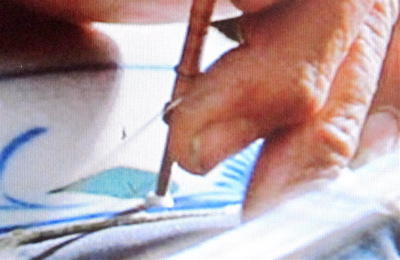

The replaced metal handle has been painted to match the body. See an earlier post, “Globular Chinese export teapot, c.1750”, with a similarly painted handle.

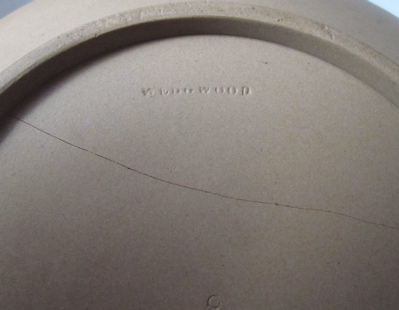

Typical pseudo Oriental marks were painted on bottom at the time of the clobbering to add “authenticity”.

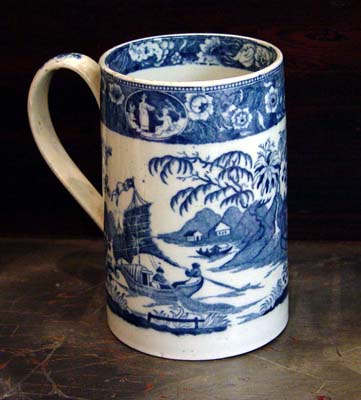

This miniature clobbered teapot of similar form shows what the original handle on my teapot might have looked like.

Photo courtesy of Grays