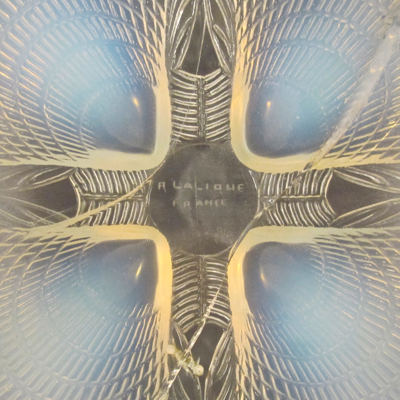

Before I travel, one of the first things I do is research the local museums, in hope of finding antiques with inventive repairs. As I am currently in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, working on a movie, in my rare time off I have been searching for make-do’s in local museums. Last weekend I finally hit pay dirt.

This past Saturday, I spent a few hours at the spectacular Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, home to one of the best collections of Islamic decorative arts in the world. Much to my surprise and delight, the museum is filled with many stunning examples of inventive repairs. The wide range includes silver, brass, and wood replacement lids, stems, handles, knobs, and spouts; made in China, Europe, and the Middle East. Strangely, I did not see any examples of staple repair, although I bet some pieces do exist, buried deep within their storage vaults.

Here are some of my favorite pieces and their printed descriptions:

Blue and white porcelain ewer, China and Persia, 17th-19th century.

Blue and white porcelain ewer, Kangxi Period, China, 1662-1722. Blue and white porcelain rosewater sprinkler, Kangxi Period, China, 18th century.

Blue and white porcelain huqqah (sic) base, Qing Dynasty China, late 17th-18th century.

Blue and white porcelain huqqah (sic) base, Kangxi Period, Qing Dynasty, China, 17th century.

Blue and white porcelain rosewater sprinkler, China, c. 17th century.

Blue and white porcelain ewer, Qing Dynasty, China, 18th century.

Engraved brass ewer, Deccan India, 17th-18th century.

Samson pot and cover (Iznik style), France, 19th century.

Underglaze painted vase, Safavid Iran, 17th century.

Underglaze painted ewer, Iran, 17th and 19th century.

Blue and white ewer, Jailing (sic) Period, Ming Dynasty China, late 16th-17th century.