In 2011 I was interviewed for the German interior design magazine A&W Architektur & Wohnen (Architecture & Living), Germany’s answer to Elle Decor. A few months after the interview, I noticed that the story was not published and assumed it ended up on the cutting room floor, never to see the light of day. But out of the blue, I just received an email from the writer of the article, informing me that it is currently featured on pages 30-32 of the February issue. So thanks to Claudia Steinberg for writing what appears to be a wonderful article and for contacting me three years later with the unexpected and surprising news.

A helpful co-worker of mine, Henrietta Ohno, provided this “quick and clumsy translation” (her words, not mine!) but I appreciate her effort and I think you will get a general idea of the article.

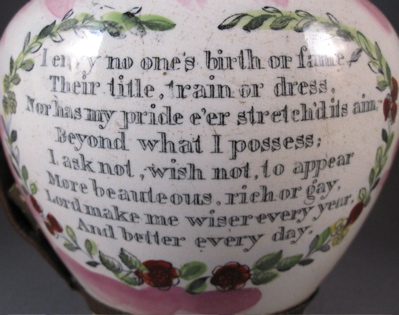

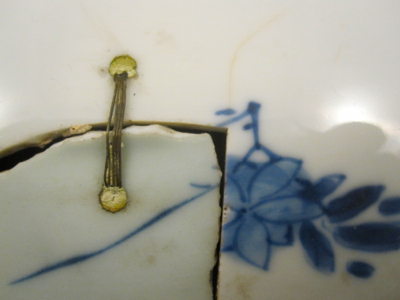

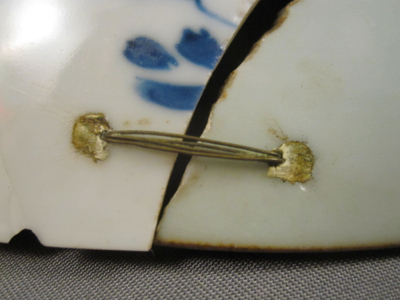

“Cemented, hobnailed, patched – the more imaginative an object’s repair the more welcome it is – because it attests affection.

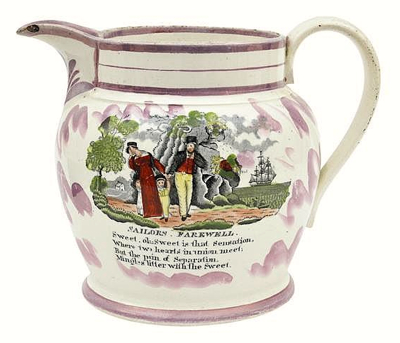

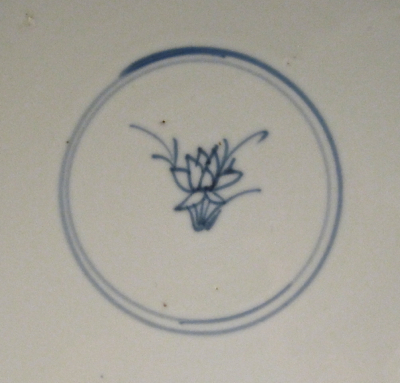

A rafter nail serves as this lead dog’s prosthesis, 42 wire clips bond together an early 19th century canary yellow ceramic cup. Four iron band-aids heal the gaping wound of a broken wooden blow from Africa. For New York interior architect and set decorator Andrew Baseman these occasionally dilettante repairs are proof of an imaginative and inventive spirit. He adores these battered objects as survivors of an era without magic glue, in which a scratch, a crack and even a missing handle did not necessarily constitute a death verdict for an object. If one listens to him, the metal strap corset doesn’t only offer a second chance to this Chinese tea pot that is missing both spout and handle. The pot also gained in character. Its restoration gives proof of an affection someone once paid their plates and cups.

Damaged articles were part of every household until the mid- 20th century. In the Post-war era with its throwaway tendencies they finally got relentlessly discarded.

Being raised a son of antique dealers from New England Andrew Baseman grew up with an innate love and respect for old objects. But from early on it wasn’t the flawless showpieces in display cases that fascinated him, but the drawer that held damaged goods. Images and phantasies of human dramas would be awakened at the sight of shards – of scolded children and discharged maids. “It is the nearly fatal accident that alters the course of the fate of damaged statue or sugar set.”, says Andrew Baseman. The “orphans” of the antique trade became his passion, a passion not everybody understands. Store owners can react with distrust or even feel offended when Andrew Baseman asks about damaged articles. What does he intend to imply when he inquires about a Chinese vase that has its repaired wound bashfully hidden from first sight?

Only in Japan, where a sensitivity for fragility and for impermanence are part of the culture, the mending of a damaged object has developed into an artform. Craftsmen of the 15th Century Kintsugi technique enobled fractures with golddust and laquer in such a way that eventually ceramic jugs and cups were willfully damanged to be repaired in the Kintsugi style.

A sense for the innate history of things can be ascribed to the British as well. Since long ago the British aristocracy has had its damaged China repaired with the help of sterling silver, even doll play dishes were mended in such lavish ways.

Whether extravagantly repaired with gold dust and silver, or with what’s at hand at the time, may it be tin, zinc, aluminum or wood – it is the visable restauration that Andrew Baseman favors over the so-called blind restauration. With one exception: a parrot lamp, a heirloom from his grandmother, had its broken off beak glued back on invisibly with state-of-the-art techniques – his personal past, it seems, he prefers unhurt and unbroken.”