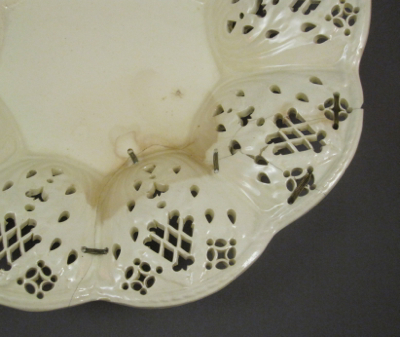

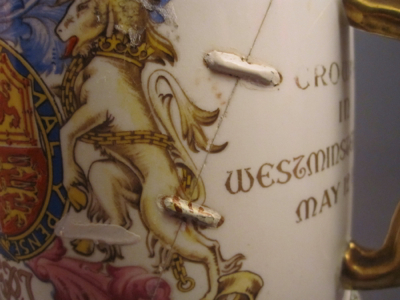

This type of pearlware pottery “Dutch” shape jug, decorated in the Oyster pattern, was manufactured in England and Wales between 1820 and 1860, although about 80% of the production of this popular form and pattern was done in Staffordshire, England. Standing nearly 5″ tall, it is hand decorated with cobalt blue underglaze and pink lustre, green, and burnt orange overglaze enamels. Although this is not a hard to find jug, I have yet to see one with this type of seemingly simple, yet elaborate inventive repair.

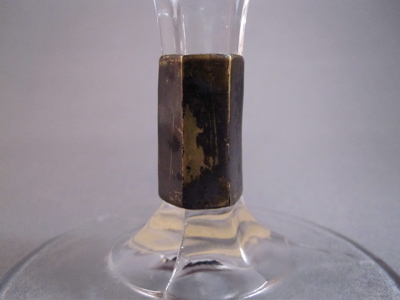

Sometime in the 19th century after the jug was dropped, causing its handle to break into four pieces, a repairer decided to reinforce the broken pieces, rather than create a new metal replacement. The simple loop handle now contains three metal rivets attached through holes drilled at each broken joint, an iron cuff at the bottom, a ring at the top attached to a rivet drilled through to the inside rim, and a splint made from two thin copper wires soldered to the ends and riveted along each joint. I applaud the anonymous repairer who took a different approach with this type of unusual repair and am glad to have the outcome of his creativity in my collection.

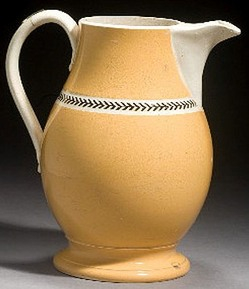

This jug with the same form and decoration has its handle intact.

Photo courtesy of Ruby Lane